|

| Unidentified maker, occasional table of red cedar with mahogany and rosewood veneers, [Sydney, NSW, about 1845] |

If we regard design as a tripartite process of production,

mediation and consumption and view it pre-eminently as one of the

manifestations of industrialisation, then we have to allow that for much of the

nineteenth century the production of furniture fell into what might be described

as a design history problematic: it was global yet persistently local; it was modern in its conception and production, yet pre-modern in the methodology of its making. The raw materials used by furniture makers were

sourced globally: from exotic timbers such as Brazilian and Indian rosewood and

mahogany – used largely for veneers, to more humble woods, such as Baltic

pine and deal, which were employed structurally. Over the course of the nineteenth century, furniture production was neither industrialised nor

entirely craft-based; and while many of the processes it made use of were increasingly

mechanised, those making it were still, largely, organised on the

pre-industrial model of master, journeyman and apprentice, although this also changed as the century wore on.

In terms of its mediation though, nineteenth century

furniture production, at least that directed for consumption by the middle and upper classes,

was entirely modern, relying predominantly for its types and forms on pattern

books, catalogues and other printed references. The use of such mediated sources

was no new thing and had characterised elements of European furniture production – particularly those directed at luxury markets – since the

rapid expansion of printed visual media in the mid-eighteenth century. The

difference was that printed material was no longer exclusive to producers but

was used, increasingly, to shape market preferences. As society commercialised,

middle-class consumers – no matter their location – were increasingly exposed

to notions of fashionability. Equally, the availability of printed sources

meant that fashionable furniture could be produced outside the metropolitan

centres, provided it adhered to the centre’s standards of quality of design and

production.

One of the best instances of this derogation of production

was the market for furniture that emerged in Australia during the late

eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Thanks to the circumstances under which

the continent was colonised by the British, we know quite a bit about the

people who moved there, what they did and what they surrounded themselves with:

convict colonies were the ideal surveillance society and, free or not, rich or

poor, their inhabitants were well observed and the results documented. The

trouble for design historians, amongst others, has been the difficulty of

matching this archived data with the objects, the things of the period. In some

instances, it’s relatively easy; in others it’s quite impossible as the vital

connection between thing and documentary context or thing and the observed

person has been lost.

|

| John Verge architect, western façade of Camden Park House, Menangle, NSW, about 1835 |

The contents of Camden Park House, the speculating termagant John Macarthur’s ‘Grecian’ style patrician villa at

Menangle, south of Sydney (John Verge, 1835) are uniquely, for a private Australian house of that date,

largely intact and well-documented. The Macarthur papers, now held at the

Mitchell Library in Sydney, retain many of the invoices and receipts for the

objects used to furnish the house from the mid 1830s. Over the past sixty or so

years, furniture and architectural historians have sought to match the invoices

with what remains in and what is known to have been in the house – there have

been a number of family settlements over the years that have led to some

dispersals. The research has led to some items of furniture, once proudly identified

as ‘made of Australian cedar by convicts on the estate’, being recognised as made of exotic timbers and

acquired from fashionable London retailers. It’s easy to make mistakes when it

comes to cataloguing furniture, particularly if you don’t have access to

sources or are unfamiliar with the timbers used. In the case of Camden Park

House such errors of classification really shouldn’t have happened given that it

accommodates an extraordinary collection of wood samples, apparently duplicates

of those collected by William Macarthur and exhibited by him at the 1855 Paris Exposition universelle.

The study of nineteenth century Australian furniture production

has been helped by publications such as Kevin Fahy, Christine Simpson and

Andrew Simpson’s Nineteenth century

Australian furniture (Sydney: David Ell, 1985) and by the development of

that invaluable resource, the Caroline Simpson Library and Research Centre, a vital component of Sydney Living Museums, formerly the Historic Houses

Trust of NSW. With their emphasis on economic, social, political and geographic

contexts, these empirical resources have contributed to a significant change in

the way Australian material culture history is researched and written. It’s an

approach emphasising the critical position that design is more than just a production

process.

While there have been furniture histories written in and

about New Zealand they tend to be decontextualized in the sense that they focus

predominantly on objects rather than ideas; narrating the thing rather than its

context. Probably the earliest New Zealand furniture history, Stanley

Northcote-Bade’s, Colonial furniture in

New Zealand (Wellington: AH & AW Reed, 1971) was remarkable in its

attempt to both identify a genealogy of furniture types and place them within a

specific, colonial, context. William Cottrell’s more recent Furniture of the New Zealand colonial era:

an illustrated history 1830-1900 (Auckland: Reed Publishing, 2006) deploys Fahy

and Simpson’s methodology along with the facilities made available by

modern digital technology to document and analyse a much broader range of types

and possible makers.

The problematic of nineteenth century colonial furniture is

evident in a piece that turned up at a recent Art+Object auction in Auckland. It was catalogued as ‘lot 715. William IV period mahogany and rosewood work

table, single frieze drawer raised on an octagonal tapering column on a

quatrefoil base on four scroll legs. W. 510 x H. 730mm’. Rather than being a

work or sewing table, it might be better described as an occasional table as,

conventionally, work tables have a cloth bag - or the fittings for one -

suspended under the top. In addition, while the table is clad with a thickly

cut mahogany (Swietenia sp.) veneer with a cross-banded Indian rosewood (Dalbergia

sp.) trim to the top, the bulk of its carcase is made of red cedar (Toona ciliata). With the exception of the drawer, which is dovetailed, the component parts of

the table are glued and screwed together and the resting surfaces of the

scrolled pads or feet protected with pressed metal ‘buttons’. There are no

labels, stamped marks or inscriptions.

Both the thick veneer and the cedar carcase suggest that the

table was most probably of colonial manufacture. Cottrell notes that New

Zealand furniture makers used Australian red cedar, possibly as early as the

1830s and into the 1840s (pp. 312-313) but certainly not in the quantities found in this piece. A more likely place of manufacture would be Australia and more

specifically either New South Wales or Tasmania. In the 1840s and 50s, Sydney

cabinetmakers such as Andrew Lenehan and Joseph Sly were certainly making

tables with quadriform bases, scrolled pads and octagonal sectioned pedestals

with Lenehan also setting the pedestals within a turned shallow concave collar

(Fahy and Simpson, plate 455). Lenehan is also known to have used rosewood

veneers on cedar carcases in the mid 1840s (Fahy and Simpson, plate 496). The turned finials under each corner are made of a different timber from the the other external parts, have a different finish and would appear to be later additions; similar finials are found on Australian furniture dating from the 1870s and 80s. They may have been added to the table to enhance its appearance in the second-hand furniture market.

|

| Title page of John Claudius Loudon’s Encyclopaedia of cottage, farm and villa architecture and furniture (London: Longman, 1846) University of Pittsburgh Library System |

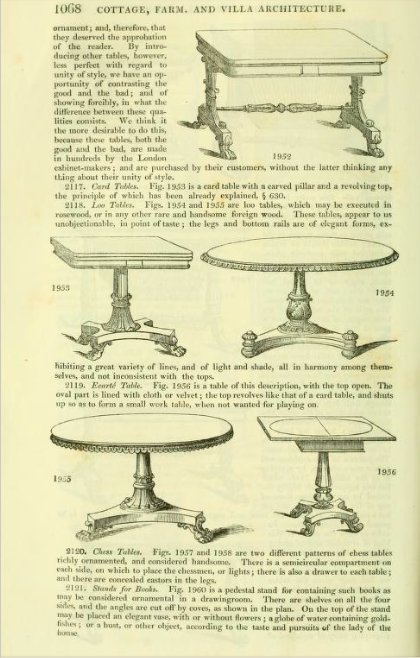

The design of the table, described by the auctioneer as ‘William

IV’ - that is it is based on a design produced between 1830 and 1837 - could

have been sourced from the maker’s own drawings, an imported example or, more

likely, on an illustrated publication. John Claudius Loudon’s Encyclopaedia of cottage, farm and villa architecture and furniture (London: Longman, 1833) illustrates an écarté

table (fig 1956) with a similar base configuration and an overall similar form

to the piece under discussion.

As Fahy and Simpson assert, Loudon’s Encyclopaedia was ‘Probably the most

popular and significant publication of the period in terms of its effect and

influence on Australian furniture forms’ (Fahy and Simpson, p. 215). Although

regarding Loudon’s prescriptions as reflecting a ‘decline in taste’, they

observe that the book was ‘Enthusiastically received in Australia’ and that

copies were in wide circulation by the 1840s and were available in popular venues such as the library of the Sydney Mechanics Institute soon after 1842. The availability of

this pattern, combined with the use of veneers, suggests that the table was

probably made about 1845.

Empirical histories are vital tools in decoding the

information embedded in objects but they tend not to be all that illuminating

when it comes to contextualising or understanding the dynamics of commodity

production, mediation and consumption. To achieve this, another approach that

is needed, one that provides a critical understanding of context,

artefacts, space and connections, across timeframes and cultures. In her

2007 paper ‘Furniture design and colonialism: negotiating relationships between

Britain and Australia 1880-1901’ (in G Lees-Maffei and R House, eds The design history reader (Oxford: Berg,

2010), pp. 478-484), Tracey Avery comments on the connection between the desire on the part of both makers and consumers for

a British appearance to furniture designs and ‘the tenuous place of Australian

timber in the hierarchy of domestic suitability.’ While Avery's focus is on a later period than

that in which the occasional table was made, her view is equally pertinent. Her conclusion is that ‘the

achievement of the appropriate furnished ‘British’ domestic interior in

Australia involved certain reassignments of meaning around style, labor (sic), and materials.’

Designed elsewhere, but veneered to express both gentility

and sameness to the culture that provided its design, the occasional table

expresses the moment in a colonial culture where the local market’s capacity

for production surpasses the social, economic and aesthetic urge to sustain haptic links with the

colonising culture.

Camden Park House continues to be a residence for the descendants of John Macarthur. It is open to the public once a year, during the second last full weekend of September. For further information see: camdenparkhouse.com.au