He aha te mea nui o te Ao? He tāngata. He tāngata. He tāngata.

Between 1967 and 1988, New Zealand, like a number of

countries in the [British] Commonwealth of Nations, had a state-sponsored

design promotion body, the New Zealand Industrial Design Council (NZIDC). It

was established through an Act of Parliament by a National party government in

1966, during the heady days of New Zealand’s short-lived embrace of the welfare

state; and it was abolished in 1988, a casual victim of the fourth Labour government’s espousal of

neo-liberal, market-driven values. The NZIDC’s survival was always tenuous:

conceived of by the left, it was brought into play by the right; initially

funded by the state, it was intended that it be funded by its primary

beneficiaries, the curiously indifferent private sector; aimed at educating

manufacturers and consumers in order to achieve greater economic efficiencies,

it was perceived by designers as being primarily an institutional support

mechanism for their practice; and intended to benefit society at large, it

ended up providing state-funded largesse for private sector management. This post

seeks to identify some of the background influences that led to the formation of this body.

States around the world have long patronised artists, including

those that we now describe as designers. Attitudes towards the idea of design

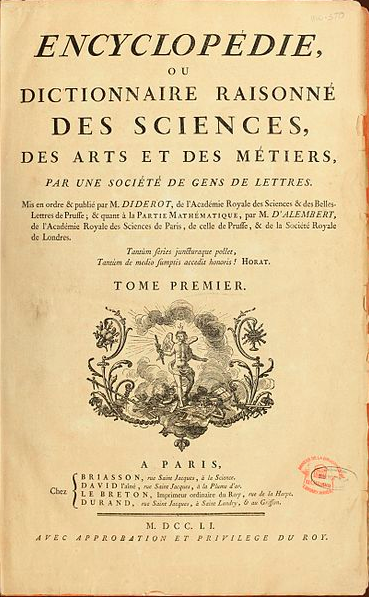

began to change in the mid-eighteenth century with the publication of Denis

Diderot and Jean Le Rond D’Alembert’s Encyclopédie

with its innovative and confronting exposition of the mechanical arts. But it

was only following the establishment of the Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers

(1794) in Paris during the French revolution that administrators and

politicians began to realise that design had a separate function to

traditional arts practice, one that abjured the idea of direct patronage in

favour of education and promotion. More important was the realisation that

design, or as it was more commonly understood, industrial art, could play a

significant part in the expansion of trade and industry.

By the early 1830s it was becoming evident in Britain that,

notwithstanding its position as the first country to embrace industrialisation,

its manufacturing was losing out to French, Prussian and Bavarian industry in

part due to the abysmal standards of the design in its manufactured

commodities. Between July 1835 and July 1836, a British House of Commons Select

Committee on Arts and Manufacture, chaired by a Liverpool MP William

Ewart, inquired into ‘the best means of extending a knowledge of the arts and the

principles of design among the people (especially the manufacturing population)

of the country’.

One outcome of the committee’s deliberations was the

establishment of twenty Schools of Design in manufacturing centres throughout

the country including schools, at Somerset House in London (1837), Birmingham

(1843) and Glasgow (1845). Another, more

visual, if transitory, legacy of the committee’s deliberations was the 1851

Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of all Nations. Both moves impacted

the distant colony of New Zealand: tiny as it was, New Zealand was a captive

market for British manufactured commodities, many of which were designed by

students of the school; and, from 1851 New Zealand participated in a number of

international exhibitions, sometimes barely visibly, and held three, although

their international character was not particularly evident. Moreover, as Ann

Calhoun has noted, New Zealand art schools established in the 1870s and 80s

employed graduates of the National Art Teacher Training Scheme – the South

Kensington System – and, more often than not, adhered to its training syllabus

with a considerable degree of verisimilitude (A Calhoun, The arts and crafts movement in New Zealand 1879-1940 (Auckland:

Auckland University Press, 2000)).

By the end of the nineteenth century, the British state’s

interest in design and industry had waned, notwithstanding increasing evidence

that it was losing the manufacturing wars, not only against its old competitors

on mainland Europe but also to the rising industries of the United States. In a

belated response, British civil servants launched a series of design-focussed initiatives, including a dedicated exhibition design organisation, the

Exhibitions Branch, located within the British Board of Trade. Following the

First World War, the same department of state launched a semi-public design

promotion body, the British Institute of Industrial Arts, which sought to

interest both manufacturers and, to a lesser degree, the public in the idea of

design; it failed.

In July 1924, Ramsay MacDonald prime minister in the

short-lived first British Labour administration, acting on the advice of the

president of the Board of Trade, Sidney Webb, established a committee ‘to

inquire into the conditions and prospects of British industry and commerce,

with special reference to the export trade.’ (Great Britain. Committee on

Industry and Trade, Factors in industrial

and commercial efficiency (London: HMSO, 1927), ii). Industrial art was one

of the factors addressed by the committee but it was not until the return of a

Labour administration that any action was taken to address the committee’s

findings. In July 1931, William Graham, president of the Board of Trade in the

equally short-lived second Labour administration, appointed a committee under

the chairmanship of a Liberal peer, Lord Gorell, that was required to

investigate and advice on the formation of a ‘standing exhibition of articles

of everyday use and good design of current manufacture’. (Great Britain. Gorell

Committee, Art & industry

(London: HMSO, 1932), p. 5).

The Gorell report prompted the formation in 1934 of the

Council for Art and Industry, an advisory body located within the Board of

Trade, chaired by Frank Pick and charged with dealing ‘with questions affecting

the relations between Art and Industry’. (Great Britain. Council for Art and

Industry, Design and the designer in

industry (London: HMSO, 1937), p. 5). Success also eluded the Council: it

upset Conservative politicians, alienated civil servants at both the Boards of

Trade and Education and ended up as the whipping boy for British failure at the

Paris Exposition International held in 1937; finally, it was suspended at the

start of the Second World War by an unconvinced Conservative government.

It was the concept of planning that rescued

state-sponsored design promotion from administrative oblivion. The adoption of

a command economy during war suddenly made a whole range of hitherto concealed

data sets available to the civil servants – many of them recruited temporarily

from the private sector – who had been charged with maximising national

economic efficiencies. What they discovered about the way British industry had

operated in the recent past shocked them into recommending drastic measures,

particularly in respect of the role manufacturing industry would play in

post-war trade. In April 1942, an official committee, titled the Sub-Committee

on Industrial Design and Art in Industry, was formed at a meeting of the

Post-War Export Trade Committee of the Department of Overseas Trade. It would

go through various permutations, be transferred between a number of departments

and would require the endorsement of a not entirely convinced coalition war

cabinet.

The result was the formation in December 1944 of the

Council of Industrial Design (CoID), the template for all the design councils

that would later be set up throughout the Commonwealth. It was charged with promoting

‘by all practical means the improvement of design in the products of British

industry’. The council was comprised almost entirely of industrialists and its

work was undertaken by an administration separate but answerable to the Board

of Trade. For its first eight years of operation it attracted substantial

government funding.

≈

Design as a subject has rarely garnered the attention of New

Zealand legislators or its civil service. Aside from a couple of copyright acts

(1886 and 1953) which parroted clause for clause earlier British legislation, debate

about design occurred only once in the New Zealand parliament when in 1925

Gordon Coates sponsored Āpirana Ngata’s Māori Arts and Crafts Bill through the

House of Representatives. So, the appearance of an Industrial Design Bill on

the legislative calendar for 1966, sponsored by the farmer-friendly, conservative,

National party government must have come as a shock not only to MPs but also to

their constituents.

However, the bill wasn’t the result of a right wing administration,

no matter its centrist gloss, suddenly converting to the idea of big government

and a planned economy, but rather a muddled compromise measure resulting from

an initiative sponsored by the previous Labour government and the brainchild of

Dr William Ball Sutch, sometime permanent secretary of the Department of

Industries and Commerce, who had been recently sacked from that position by the

bill’s sponsor, John Marshall, the minister of Industries, Commerce and Overseas Trade.

|

| John Marshall (right) speaking with an employee of the NZIDC at the New Zealand Industries Fair, Christchurch, in August 1970. Designscape 36 (1970). |

Sutch was highly-qualified: he had a PhD in economics and

political science from Columbia University in New York; he was sophisticated,

well-travelled, intellectual; pretty much of an anomaly in the New Zealand

civil service and a rarity in New Zealand society. He was a passionate

defender of the poor and oppressed, a feminist avant la lettre, a committed nationalist and an ardent controversialist.

Sutch was also a remarkable administrator and, under his watch, the Department

of Industries and Commerce became the most professional department of state in

the New Zealand public service. John Marshall was the antithesis of Sutch; a

lawyer by training with an interest in evangelical Presbyterianism, rugby and

the traditional arts. He had a reputation as a ‘skilled parliamentarian’ and later,

for some nine months, was prime minister. He is best remembered as heading the

New Zealand team attempting to negotiate favourable terms of trade following

Britain’s entry into the European Economic Community.

It’s difficult to know when Sutch became aware of the CoID

or what prompted his thinking that forming a design council in New Zealand was

a good idea although we have some inkling when, in a 1960 letter to the British trade commissioner in Wellington, he recalled that he

was already:

familiar with the work of the

[CoID] and when I was in London during the trade discussions [in April 1958] I

saw something of their work and had discussions with the man who has now been

appointed in charge [Paul Reilly]. I brought back with me a fair body of

material and in addition the Department [of Industries and Commerce] has been

subscribing for some time to their journal ‘Design’. My thought is that it is

about time New Zealand had a similar organisation, but of course it cannot hope

to be as powerful or achieve the results of the UK one (Archives New Zealand, IC W1926 57/1/6 vol 1 box

1797).

What we do know is that Sutch’s interest in design formed part of a

wider approach to reinventing the New Zealand industrial landscape that he

began to develop shortly after returning to the country in 1951 after six years

in Sydney, New York and London. Sutch’s vision was for a country that was

economically as well as politically independent; one that produced more than

just the by-products of grass; and one that ensured that all its people were

able to live well and without want.

Sutch’s thinking on the industrial policy had been galvanised by

a realisation that the country could no longer depend on the export of unprocessed

agricultural commodities to Britain for the maintenance of its prosperity. These

aims were clearly articulated in a speech ‘The next two decades of

manufacturing in New Zealand’ he delivered to the 1957 conference of the

Australasian Association for the Advancement of Science.

As the country grows,

New Zealand’s main assets can only be the skill, experience and intelligence of

her people. Small countries like Finland, Denmark or Switzerland have even

fewer natural resources than we have. Yet because of the skill of their people

they are important manufacturing countries. Highly-paid labour should connote

highly-skilled labour. New Zealand’s present pre-occupation with the tariff may

be too negative approach. Should we not be more concerned with producing goods

which have as their main ingredient not raw materials but brains and skills?’ (W

B Sutch, The next two decades of

manufacturing in New Zealand (Wellington: [New Zealand] Department of

Industries and Commerce, 1957), p. 21).

His contention, his dream you might say, was that a local

design promotion body would be a critical element in this intellectually-driven

industrial renaissance. In Sutch's view New Zealand's future lay with its people and not on the production of grass. It was a stance that went against pretty much everything the still rural-dominated National party stood for.

Sutch wasn’t the first New Zealander to respond to

the British design initiative; far from it. The Wellington-based Architectural Centre

Inc, established in 1946 and with which he was involved, actively promoted

design matters. In Auckland, architects and those connected however remotely

with the practice of design had formed the short-lived Auckland Design Guild in

1949. And in Christchurch, a well-connected indent agent, Roger Lascelles,

sought to establish a modern design retail outlet, ostensibly inspired by the CoID’s

Design Centre in Haymarket, which had opened in 1956. Lascelles’ was no slouch when it came to pushing his barrow and his agitation resulted in

the formation in December 1959 of the relatively well-funded Design Institute

of New Zealand, a body that initially seems to have been entirely devoid of designers. However, looking at the surviving documentation, it seems clear

that Lascelles failed to comprehend either the purpose and nature of the CoID

or its governance. Later Lascelles claimed that he had been appointed ‘a

representative’ of the CoID; indeed, by 1963, he was listed as an 'overseas correspondent' of the CoID's Design periodical. However, correspondence from 1960 between the CoID

and the New Zealand Department of Industries and Commerce indicates that far

from entering into a formal relationship either with him or the Design

Association, the CoID had doubts as to their status. Lascelles later attributed the failure of his connection with the CoID to Sutch’s

‘interference’ but neither he nor the Design Association had the resources, let

alone an understanding of what comprised a design promotion body, to run such

an organisation.

From an indent agent’s perspective, Sutch was the

devil incarnate in the sense that the Department of Industries and Commerce played a

significant role in determining not only the country’s tariff regime but also

its import licensing system. Importers had been demonising the latter control procedure

since its introduction in 1938 and they found considerable support for their

actions amongst National party politicians. Notwithstanding all evidence to the

contrary, a significant tranche of New Zealand’s more affluent classes firmly

adhered to the belief that New Zealand consumers were being denied access to

the good design commodities that were widely available in the United States and

Europe. So, in a somewhat bizarre combination of political opportunism and

provincial ignorance, modernism, conventionally regarded by the country's dominant media as a tool of the socialist

state, became a rallying call for the traditional right.

There weren’t all that many designers working in New Zealand

in the late 1950s, rough estimates from the Department of Industries and

Commerce suggested there were about twenty, including tertiary level teachers of design. Most

of those few that had been trained through the art schools survived by school

teaching; others migrated; and a select few were employed in support roles by companies such as the white goods manufacturer Fisher & Paykel Ltd and the ceramic manufacturer Crown Lynn Potteries Ltd. The country’s small manufacturing sector was largely

ignorant of design issues, preferring to copy, usually badly, popular overseas

models. But if the importers envisaged Sutch as the devil, the designers

weren’t far behind, identifying the department as having ambitions to prescribe

how design was practised, making it subject to ‘the dos and don'ts’ of

government regulation. But design councils weren’t about organising designers,

let alone subjecting their work to the rigours of regulation. In their initial

form, the design councils were about improving trading prospects; about

educating manufacturers and consumers to the efficiencies of ‘well-designed’

commodities; it was only later, when the wanting status of design education

became apparent, that Sutch sought to recruit education to his vision of a

modern, industrial economy and to provide designers with the institutional support necessary for the development of the practice in New Zealand.

Unlike the various voluntary design appreciation societies

that emerged in New Zealand following the Second World War, Sutch was in the

unique position of being able to do something about turning his dream into

reality. This came about with the election of a Labour administration in

November 1957 and his subsequent appointment as permanent secretary. Throughout

1958 Sutch seems to have reconfigured the department, transmogrifying what was

essentially a loose assemblage of time-serving administrators into a modern

administrative department of state, focussed on providing politicians and the

public with informed, impartial advice based on properly undertaken empirical

research. And in early 1959 Sutch established a design study team within the

ministry, which comprised not only economists and (eventually) a designer, but

also investigators and researchers who, through the trade commissioner

service, had access to information, both local and international, hitherto

unavailable to New Zealand. The outcome of the study team’s work not only laid

the foundation of the NZIDC but prompted a wider debate about the role and

function of design in a modern economy.

More information on the formation of the New Zealand Industrial Design Council can be found in my paper ‘Modernizing for trade: institutionalizing design promotion in New Zealand 1958-1967’, Journal of Design History, 24:3 (2011), pp. 223-239. <https://doi.org/10.1093/jdh/epr021>.

More information on the formation of the New Zealand Industrial Design Council can be found in my paper ‘Modernizing for trade: institutionalizing design promotion in New Zealand 1958-1967’, Journal of Design History, 24:3 (2011), pp. 223-239. <https://doi.org/10.1093/jdh/epr021>.